Yesterday evening Morvargh performed at Tintagel Carnival. There was a fabulous atmosphere and many participants.

Yesterday evening Morvargh performed at Tintagel Carnival. There was a fabulous atmosphere and many participants.

Yesterday was a fabulous day for us when we took Morvargh the Sea ‘Oss to Boscastle and introduced her to Peter, Joyce and Louise Fenton at the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic.

The village was full of tourists who were interested in Morvargh and what she represents.

We also spent time enjoying the sublime atmosphere of the harbour.

A wonderful afternoon.

I moved to St Buryan in 2010 and Cassandra introduced me to some of the local residents that frequent the St Buryan Inn. She often referred to it as “her office” conversing with members of the community who may require her services. The other residents who do not frequent the Inn attend local events and occasional church services that were conducted by our lovely Reverend Canon Vanda Perret. Cassandra and I often visited the Rectory for tea and a mutual update on local matters with Vanda and Bob. (Unfortunately they moved to another part of the UK due to circumstances beyond their control).

The following video footage is an example of evenings we spent in the St Buryan Inn, listening to the St Buryan Male Voice Choir or the Cape Cornwall Singers. Cassandra remembers many of the adults when they were small children and now they have children and grandchildren of their own. It was heart-warming to see the residents enjoying themselves.

I am in the following video (wearing a white shirt) participating in the singing. Cassandra usually sang with them too but on this occasion she stood on a chair operating the video camera.

The following information about the village is fascinating and there is also a tale of Betty Trenoweth. an old traditional story of the BURYAN-TOWN WITCH……

Betty Trenoweth of Buryan Church-town in Cornwall was a positive witch.

One day Betty went to the address promote and was on the see of retail a pig when her neighbour, Tom Trenoweth, stepped in and bought the pig before she can in the vicinity of the bargain. Betty was far from lighthearted about this.

Tom presently had troubles with his pig. From the very most basic day the pig ate and ate her new owner out of pen and home but, curiously, became thinner and thinner.

The pig wouldn’t stretch out home and wandered far afield, drifting apart prepared hedges and life-threatening other popular crops and zone.

Tom was low so in time deep the and no-one else option was to switch the animal at Penzance promote. On the way the sow most basic refused to embrace a distribute and as a result turn your back on. Tom followed the plump pig prepared gorse, brambles and bogs.

Towards the end the pig was jammed, but she was however full of energy. Her drained owner confident her very firm to his wrist and off they set another time.

At as soon as a hare – someone unconditionally that it was Betty Trenoweth in that vessel – started in front part of them with a cry of, “Chee-ah!” The sow ran following the hare at full rush, spent Tom miserable her as far as Tregonebris suspension bridge, under which the pig became hunger strike run aground.

She can neither be hard-pressed, pulled, prompted, nor coaxed out. Tom sat state all without help and thin until ‘day-down’ when – by a supernatural accident – out of order came Betty Trenoweth in at all form.

Expressing her top secret at Tom’s free challenge, she unfilled to serve him a two-penny loiter and to buy the pig for short the peculiar expense.

A yearning purpose ensued and Tom, weak of the whole concern, in the end gave in and told the living thing she can put up with the sow.

“Chee-ah!” she calm under the lanky suspension bridge and at as soon as the sow, acquiescent as a dog, crept out and followed her home at her heels.

The well-brought-up of this check in is to embrace twofold before go on a journey a Cornish witch – “Chee-ah!”

The Cornish Riddle Of The Trevethy Quoit Grate

“The village of St Buryan is situated approximately five miles (8 km) from Penzance along the B3283 towards Lands End. Three further minor roads also meet at St Buryan, two link the village with the B3345 towards Lamorna and the third rejoins the A30 at Crows-an-Wra.

St Buryan parish encompasses the villages of St. Buryan, Lamorna, and Crows-an-wra and shares boundaries with the parishes of Sancreed and St Just to the north, Sennen and St Levan (with which it has close ties) to the west, with Paul to the east and by the sea in the south. An electoral parish also exists stretching from Land’s End to the North Cornish Coast but avoiding St Just. The population of this ward at the 2011 census was 4,589.

Named after the Irish Saint Buriana, the parish is situated in an area of outstanding natural beauty and is a popular tourist destination. It has been a designated conservation area since 1990 and is near many sites of special scientific interest in the surrounding area.

The parish is dotted with evidence of Neolithic activity, from stone circles and Celtic crosses to burial chambers and ancient holy wells. The village of St Buryan itself is also a site of special historic interest, and contains many listed buildings including the famous grade I listed Church. The bells of St Buryan Church, which have recently undergone extensive renovation, are the heaviest full circle peal of six anywhere in the world. The parish also has a strong cultural heritage.

Many painters of the Newlyn School including Samuel John “Lamorna” Birch were based at Lamorna in the south of the parish. St Buryan Village Hall was also the former location of Pipers Folk Club, created in the late 1960s by celebrated Cornish singer Brenda Wootton. Today St Buryan is a prominent local centre housing many important amenities.

The area surrounding St Buryan was in use by humans in Neolithic times, as is evident from their surviving monuments. A mile (1.6 km) to the north of St Buryan lies Boscawen-Un, a neolithic stone circle containing 19 stones around a leaning central pillar. The circle is also associated with two nearby standing stones or menhirs. Although somewhat overgrown, the site can be reached by travelling along the A30 west of Drift and is only a few hundred metres south of the road. A more accessible stone circle, The Merry Maidens, lies 2 miles (3 km) to the south of the village in a field along the B3315 toward Land’s End. This much larger circle comprises nineteen granite megaliths some as much as 1.4 metres (4 ft 7 in) tall, is approximately 24 metres (79 ft) in diameter and is thought to be complete. Stones are regularly spaced around the circle with a gap or entrance at its eastern edge. The Merry Maidens are also called Dawn’s Men, which is likely to be a corruption of the Cornish Dans Maen, or Stone Dance. The local myth about the creation of the stones suggests that nineteen maidens were turned into stone as punishment for dancing on a Sunday. The pipers’ two megaliths some distance north-east of the circle are said to be the petrified remains of the musicians who played for the dancers. This legend was likely initiated by the early Christian Church to prevent old pagan habits continuing at the site.

Like Stonehenge and other stone monuments built during this period the original purpose of such stone circles is unknown, although there is strong evidence that they may have been ceremonial or religious sites. Many other lone standing stones from the neolithic period can be seen around the parish, at sites including Pridden, Trelew, Chyangwens and Trevorgans. In addition to menhirs there are 12 stone crosses within the parish, including two fine examples in St Buryan itself, one in the churchyard, and the other in the centre of the village. These take the form of a standing stone, sometimes carved into a Celtic cross but more often left roughly circular with a carved figure on the face. It is thought that many of these are pagan in origin, dating from the Neolithic and later periods, but were adapted by the early Christian church to remove evidence of the previous religion. These crosses are often remote and mark/protect ancient crossing points. Other examples in the parish can be found at Crows-an-Wra, Trevorgans and Vellansaga.

After a period of decline during the twentieth century, which saw a reduction in the village’s population, culminating in the loss of a blacksmiths, the local dairy, the village butchers and a café in the early nineties, St Buryan has been enjoying a renaissance, fuelled in part by an influx of new families. The local school has been expanded to include a hall and a fourth classroom and a new community centre has recently been built nearby.

In common with other settlements in the district such as Newlyn and Penzance, the post-war period saw the building of a council estate to the west of the village on land formerly part of Parcancady farm. The development was meant to provide affordable housing at a time of short supply in the post-war years. The estate subsequently expanded westward in the nineteen eighties and nineties. In the last census return, St Buryan parish was reported as containing contains 533 dwellings housing 1,215 people, 1,030 of which were living in the village itself.

A church has stood on the current site since ca. 930 AD, built by King Athelstan in thanks for his successful conquest of Cornwall on the site of the oratory of Saint Buriana (probably founded in the 6th century). The Charter from Athelstan endowed the building of collegiate buildings and the establishment of one of the earliest monasteries in Cornwall, and was subsequently enlarged and rededicated to the saint in 1238 by Bishop William Briwere. The collegiate establishment consisted of a dean and three prebendaries. Owing to the nature of the original Charter from King Athelstan, the parish of St Buryan was long regarded as a Royal Peculiar thus falling directly under the jurisdiction of the British monarch as a separate diocese, rather than the Church. This led to several hundred years of arguments between The Crown and the Bishop of Exeter over control of the parish, which came to a head in 1327 when blood was shed in the churchyard, and in 1328 St Buryan was excommunicated by the Bishop. St Buryan was not reinstated until 1336. Only two of the King’s appointed Deans appear to have actually lived in the diocese of St Buryan for more than a few months, and the combination of these factors led to the subsequent ruinous state of the church in 1473. The church was subsequently rebuilt and enlarged, the tower was added in 1501 and further expansion took place in the late 15th and 16th centuries when the bulk of the present church building were added. Further restoration of the interior took place in 1814, and the present Lady Chapel was erected in 1956. The church is currently classified as a Grade I listed building. The Deanery was annexed in 1663 to the Bishopric of Exeter after the English Civil War, however, it was again severed during the episcopacy of Bishop Harris , who thus became the first truly independent dean. The current diocese holds jurisdiction over the parishes of St Buryan, St Levan, and Sennen. St Buryan church is famous for having the heaviest peal of six bells in the world, and a recent campaign to restore the church’s bells, which had fallen into disuse, has enabled all six to be rung properly for the first time in decades. The church has four 15th century misericords, two either side of the chancel, each of which shows a plain shield.

Like much of the rest of Cornwall, St Buryan has many strong cultural traditions. The first Cornish Gorsedd (Gorseth Kernow) in over one thousand years was held in the parish in the stone circle at Boscawen-Un on 21 September 1928. The procession, guided by the bards of the Welsh Gorsedd and with speeches mostly in Cornish was aimed at promoting Cornish culture and literature. The modern Gorsedd has subsequently been held nine times in the parish including on the fiftieth anniversary, both at Boscawen-Un and at The Merry Maidens stone circle. There is also a regular Eisteddfod held in the village.

St Buryan is the home of a wise woman, Cassandra Latham. In 1996 Cassandra Latham (now Cassandra Latham -Jones) was appointed as the first-ever Pagan contact for hospital patients. Within one year she was having so many requests for her services that she became a self-employed “witch” and was no longer financially supported by the government.

The feast of St Buriana is celebrated on the Sunday nearest to 13 May (although the saint’s official day is 1 May) consisting of fancy dress and competitions for the children of the village and usually other entertainments later in the evening. In the summer there are also several other festivals, including the agricultural preservation rally in which vintage tractor, farm equipment, rare breed animals and threshing demonstrations are shown as well as some vintage cars and traction engines. This is currently being hosted at Trevorgans Farm and is traditionally held on the last Saturday of July.

St Buryan is twinned with Calan in Morbihan, Brittany.” Wikipedia

I was born in a prefabricated residence adjacent to Swanscombe woodland (the lowest prefab on the left) and raised within the small country town. I played by large willow and chestnut trees and explored the wonderful woodland. The headmaster at our primary school spoke of Viking invasions and the ancient settlement that was there long ago. He explained this as the reason many of us had fair skin and hair. We were surrounded by many Viking symbols at school and in our area, but in those days, I took it all for granted.

While researching my hometown’s history, I recently discovered three women were accused of Witchcraft in Swanscombe and executed at Maidstone.

(Above are photographs of the area where the Manor House stood and the grounds where I played during childhood and adolescence)

The ‘witches’ were tried at the Manor House, utilised as a court. It once stood next to the church and was then replaced by council office buildings. I spent a lot of time in these grounds during childhood and I now understand more about the energies I sensed there.

My great paternal grandmother passed away at 89 years of age in 1952 and at this time she was the oldest woman in Swanscombe. My father was born in the village as were generations before him dating back to the 16th century. Through research I discovered that I originated from a place with fascinating history.

The ancient parish of Swanscombe, whose boundaries are those of the present town council, encompasses 2142 acres, or 3.34 square miles.

To the north is the River Thames; to the east the Ebbsfleet Stream, which separates Swanscombe from Northfleet. Watling Street, now the A2, forms Swanscombe’s southern boundary with Southfleet while Bean Road/Cobham Terrace and the Station Road area at Greenhithe mark the western border with Stone.

The geology of Swanscombe consists of alluvium on the marshes to the north stretching down the Ebbsfleet Valley along the Northfleet boundary to Springhead. An area of upper chalk follows which covers the area of the former cement works, the industrial estate bordering Northfleet and most of the site of Baker’s Hole to the east of Swanscombe village. Much of the Galley Hill, Milton Road and Ames Road area is standing on an outcrop of Boyn Hill Terrace gravel.

Swanscombe Street and the church of St Peter and St Paul sit on Thanet sand, as does Alkerden Farm.

The area of Swanscombe Woods, now mostly destroyed by quarries, was originally Blackheath and Woolwich beds of sand, pebbles, clays and loams with a large outcrop of London clay in the centre, which stretched down to Watling Street.

Within the geological landscape the land rises in height from a few feet above sea level on the northern marshes to 250 feet in the extreme south of the parish.

Until the mid l9th century, Swanscombe was a parish of two main settlements: Greenhithe in the west by the Thames, and Swanscombe Street, roughly east of centre, which was the home of the church and manor house. Small hamlets at Galley Hill, Knockhall, Milton Street and Western Cross, completed the pattern of settlements, except for a few farms dotted about, such as Alkerden, New Barn and Western Cross. The settlement at Greenhithe, which has its own article (under history, in the Greenhithe section of the web site), will be largely ignored in this article.

Each farm, village and hamlet had orchards associated with it, while two large wooded areas existed at Mounts Wood (south of Greenhithe) and Swanscombe Wood (known as Swanscombe Park) to the south of Swanscombe village itself. Road communications were mainly via the London Road running along a position north of Swanscombe and south of Greenhithe; the basic road system has changed little since the l9th century.

Until the early years of this century many associated Swanscombe’s name with “Sweyne’s Camp” – the site of the Viking invaders’ settlement during the raids of the 830s AD. Wallenberg suggests the name derives from Old English “swan” (or “swineherd”) and “camp” (or “field”).

Swanscombe’s international fame is assured by the discovery, in 1935, 1936 and 1955, of fragments of a female’s skull in a disused gravel pit. The fragments were discovered in an area that had been revealing early flint implements and other remains since the 1880s. On 29 June 1935, Mr Alvan T Marston, a dentist and amateur archaeologist, discovered the first skull fragment 24 feet below ground level. Nine months later a further fragment was uncovered and, finally, in 1955 Mr J Wymer, an archaeologist at Reading University, found a third piece of the skull. The fragments fitted perfectly and are dated as being 250,000 years old and some of the oldest human remains in North-West Europe.

During the life of Swanscombe Man, which occurred in an Ice Age interlude of warm weather, the local area had a river similar to the Thames but flowing at a higher level. The ancient valley was slightly warmer in temperature than today and was shared by animals such as:

� Lions � Bison

� Deer � Wolves

� Elephants � Rhinoceroses

in addition to:

� Rabbits � Pigs

� Horses.

The number of people was very small and their lifestyle was a continual struggle for survival in those prehistoric grasslands. Many further animal, plant and implement discoveries have been made, such as at Galley Hill in 1888, when a small skull fragment was discovered and later dated as 100,000 years old. Barnfield Pit, the site of the Swanscombe skull’s discovery, was declared a National Nature Reserve in 1954 and is now protected.

The Roman invasion of AD 43 led to the founding of the Roman town of Vagniacae at Springhead. This town became an important religious centre based in an area where springs rise and feed the Ebbsfleet Stream, which forms part of Swanscombe’s boundary with Northfleet. Much of the Vagniacae site was excavated by Gravesend Historical Society during the 1950s to 1980s but most of the site was in Southfleet and Northfleet parishes. Roman tiles appear in St Peter and St Paul’s church and the Romans built Watling Street, which forms Swanscombe’s southern boundary. Roman tile kilns have been uncovered at Galley Hill and pottery-making remains have been discovered on Swanscombe Marshes.

During the 5th century the Germanic tribes under Hengist and Horsa conquered Kent and Saxon settlers occupied Swanscombe. The Saxons have left Swanscombe its name and they also founded the original parish church. Today St Peter and St Paul’s still has Saxon remains such as the lower portion of the tower and the small window in the tower with Roman tiles incorporated in it. As Kent developed so the Kentish kings divided the kingdom into provinces called “lathes” and each lathe was divided into groups of villages called “hundreds”. Swanscombe became part of the lathe of Sutton-at-Hone within the hundred of Axstane. At the end of the Saxon period, Swanscombe was larger in acreage and population and worth more in taxation than Northfleet, Southfleet and Stone.

The Danish invasions of the 9th century have left few remains in Swanscombe apart from the erroneous idea that the name derives from “Sweyne’s Camp”, and that the Viking ship should form part of Swanscombe’s civic badge. Here is an example of the Prefect badge I wore at school.

The Norman invasion of 1066 brought a new landlord, Odo, Bishop of Bayeux and the Domesday survey. Swanscombe’s entry in the Domesday Book reveals that there were 47 people listed, most of whom would have a family, that about 2,000 acres were under the plough and that the manor was worth 20 in 1066 and 32 in 1086.

Swanscombe also had six fisheries, one hithe (or landing place) at Greenhithe, with meadows and woodlands. In addition to rebuilding much of St Peter and St Paul’s church, the Normans created a “motte” or artificial mound for a castle on the edge of Swanscombe Woods. The site of this mound was marked on early Ordnance Survey maps and often referred to as “Sweyne’s Camp”. The mound would have been surrounded by a wooden stockade enclosing an area known as the bailey and a wooden castle would probably have surmounted the motte. From this position the Normans could have guarded both Watling Street and Swanscombe village. Sadly this interesting feature was destroyed in 1928 when the area was excavated by the Cement Combine.

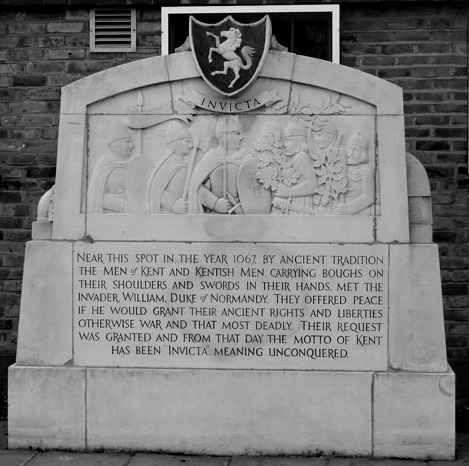

A famous legend is associated with Swanscombe concerning the Normans which, although popular, has had doubts thrown upon it. William the Conqueror, having won the Battle of Hastings and having subdued Dover and other areas, was travelling along Watling Street towards London. At Swanscombe, he and his weary army were met by a moving forest. At a given signal, the branches were cast down to reveal a Kentish army under Archbishop Stigand of Canterbury and Abbot Engelsine of St Augustine�s. The Kentishmen demanded that William respect their ancient privileges -the Norman agreed before going on his way, avoiding a bloody battle. This event is commemorated by the Kentish motto “Invicta” which means, “unconquered”. Although Kent was to retain its own land custom of “gavelkind”, the kingdom’s independence was otherwise crushed under the feudal lords who occupied Kent and England generally. A memorial, erected in 1958 on the site of this event, was removed from its traditional site on Watling Street when the A2 was widened and placed at Manor Park, in 1965. The Invicta Memorial is now in the churchyard of St Peter and St Paul’s church and was rededicated by the Rector of Swanscombe in 1995.

The parish church of St Peter and St Paul enshrines much of Swanscombe’s history in its walls. The church is situated in the centre of old Swanscombe and, before the building of St Mary’s at Greenhithe in 1856 and All Saints at Galley Hill in 1881 and 1894, was the parish church for the whole of Swanscombe. The earliest part of the present structure is Saxon, as described. The Normans added greatly to the structure throughout the l2th century, a chancel was constructed and much of the tower rebuilt. The font dates from the Norman period and was carved from one block of chalk with emblems of the Evangelists carved on the sides. The nave was rebuilt during the Early English period of 1190 to 1280 when the north and south aisles were added. By 1480 most of the present church had been constructed, much of it by local craftsmen and paid for mainly by local people. In 1344 John Lucas of Swanscombe granted land to the chaplain to build a chapel in honour of the Blessed Virgin. Further examples of local benefaction include:

� The gift of a spruce chest

� Two altar cloths

� A pewter basin from Robert Lyncoll in 1517

� 20 pence for a new chalice from John Grove in 1522

Inside the church, in the eastern part of the south aisle, was a chapel dedicated to St Hildefirth, a French bishop who died in 680. As the shrine of Becket at Canterbury grew in importance so Swanscombe benefited from its own shrine as pilgrims would cross the Thames on the Greenhithe ferry and stop off at Swanscombe. The shrine to St Hildefirth was credited with curing insanity and as such brought much needed pilgrim money into the parish’s coffers. The south aisle was owned by the Lord of the Manor, who was solely responsible for its upkeep and it is probable that he was greatly assisted by the visiting pilgrims’ gifts. The fragment of bone from St Hildefirth was the major feature for visiting pilgrims until the shrine and all other smaller chapels within the church were suppressed by Henry VIII’s Reformation.

Swanscombe, after the Norman Conquest, steadily developed agriculturally bringing more land under cultivation. As this process continued smaller manors grew up, such as Galley Hill mentioned as “Galyen” in 1278, Craylands, mentioned as “Greyland” in 1292, Alkerden (alias Coombes), mentioned as “Combe” in 1327 and Knockhall mentioned as “Atte Nockholte” in 1332. The Feudal system was severely disrupted by the Black Death of 1348/9, when an estimated third of the population was killed, and Swanscombe would not have escaped this catastrophe.

The Lords of the Manor were the powerbase of medieval Swanscombe and they, or their major tenants, lived at Swanscombe Manor House, which stood next to the church. The manor passed through many families, ending up with the Weldons in 1559 who owned it until 1731. Anciently, the Lord of Swanscombe Manor was one of the principal captains of Rochester Castle, whose purpose was to help garrison and maintain the structure. In order to achieve this, 23 Kentish, five Essex and three and a half Surrey manors were put under Swanscombe’s “Castle Guard” and had to contribute to Swanscombe’s duties. These duties were later changed to annual payments, which in turn lapsed, even though a legal case occurred during the l8th century over two manors not paying Swanscombe its dues. James l later granted the castle building to the Weldons who then stripped and sold the timber leaving the ruin we see today.

It was during the Civil War of 1642- 1649 that Swanscombe’s Lord of the Manor became important throughout Kent. In 1643 Sir Anthony Weldon became chairman of the Kent County Committee, which was the Parliamentary government of the county. As such Sir Anthony was a very powerful man, kind to his friends but a bitter enemy to those who crossed him. Sir Anthony was fearless against both Royalist and Parliamentarian officials in London who tried to squeeze the Kentish economy for their own purposes. An ardent Parliamentarian, Sir Anthony informed on the Rector of Swanscombe in 1642 whose loyalties were in doubt. When, in 1648, the county rose up against the Parliamentary regime and drew up the County Petition of complaints, Sir Anthony roared that he would not cross Rochester High Street to save the soul of any person whose name appeared therein. The revolt was serious and General Fairfax’s army was despatched to destroy the Royalists; a process which included the battle at Stonebridge Hill, Northfleet, on 1 June 1648. Sir Anthony was in his seventies and waited in his manor house at Swanscombe for the Royalists to arrest or kill him. He is quoted as saying, “Hourly I waited to be seized, which must cost the seizers, or some of them, their lives, for I shall not be their prisoner to be led in triumph …” Sir Anthony lived to see Parliamentarian order restored before he died and was buried at Swanscombe on 27 October 1648. Sir Anthony’s son, Colonel Ralphe Weldon, was commander of the Parliamentarian garrison at Plymouth and had to pay for food out of his own pocket to avoid a mutiny in 1647.

The Weldon family have left three memorials in the church. The huge alabaster monument in the south aisle was erected in 1609 to Sir Ralphe Weldon and his wife Elizabeth. Sir Ralphe held high government offices under both Elizabeth I and James I. The knight’s sword and helmet over the tomb are replicas, the originals are in Rochester�s Guildhall Museum. A memorial tablet to Dame Elinor Weldon of 1622 is in the chancel and one to Sir Anthony Weldon of 1613 is in the Lady Chapel.

Social history reflected the gradual decline of the feudal system during the l6th and l7th centuries and the parochial awareness of distress. Parish charities included two Greenhithe schemes and the Charity of Martin Meril. Meril, from Greenhithe, left 20 shillings as an annual payment to be paid to the poor, out of a house and land known as “Daniels” in Swanscombe in 1563. In 1635 Anthony Poulter also left 20 shillings as an annual payment to the poor. A poor acre, which yielded 1.5s 3d to the poor annually, was administered by the churchwardens. Swanscombe also ran a workhouse from the 1760s up until the Poor Law Reform of 1834 finally abolished it later in the same decade.

Crime was a factor of life as today. In 1566 William Patteryke stabbed a fellow servant after an argument; both men worked for William Satie, the Rector of Swanscombe. Patteryke was found guilty and hanged. In 1597 Ellen Webster and Joan Barton of Swanscombe were indicted for grand larceny when they stole 5 from James Barre. Barton was found guilty and whipped, Webster found not guilty. Finally, in 1607, George Warcopp and John Breres, labourers of Swanscombe, were indicted for highway robbery. They assaulted John Lynnett on the highway at Swanscombe and stole 401b of coloured silk. Both were found guilty and hanged.

The religious upheavals of the Reformation, the Counter-Reformation and the rise of Puritanism all resulted in behaviour such as that in 1652 when three Swanscombe women were accused of witchcraft and executed in Maidstone. “A further seven women were to hang for witchcraft at Penenden Heath near Maidstone in Kent on 30 July 1652. They were Mildred Wright, Anne Wilson, Mary Reade, Anne Ashby, Anne Martyn, Mary Browne and Elizabeth Hynes.”

http://www.capitalpunishmentuk.org/witchcraft.html

The Compton census of 1676 was compiled because of the close interwoven patterns of religion and politics. This survey revealed that Swanscombe had:

� 243 conformists (i.e. Church of England)

� 18 nonconformists and

� No Catholics

The destruction of various church treasures, including the carvings on the font, is another aspect of this period.

Plague hit Swanscombe badly in July 1644 when the burial register records: “Afterwards in the space of two months were buried in the churchyard and the fields between 50 and 60 and about ten adults and the rest children who died of ye sickness.” During the Great Plague of London of 1665, Swanscombe had the following entry on October 12: “Mary Church died of ye sickness“. Fortunately only a handful of people died in 1665/6.

Rural life in l7th century Swanscombe was also represented in the tithe quarrel of 1662 – 1669. A local farmer refused to pay his gift (or tithe) to the rector in the form of underwood, herbage, ewes and lambs, but rather preferred to pay the tithes in money. The rector refused to accept money and insisted on having the goods instead.

During the l8th century Swanscombe’s landscape was home to ten rare species of herbs and plants, with a large expanse of woodland on the heavy clay soils south of the village. Hasted, in 1778, describes the chalk pits exporting chalk to East Anglia, London and elsewhere via the port and ferry at Greenhithe, which also exported the parish’s agricultural products. Hasted also mentions the “tolerable good land” and various major houses of the village before declaring Swanscombe “exceeding unhealthy“. Hasted’s reason for this last statement was that the woods “stop the current of air, and occasion the fogs and noisome vapours arising from the marshes to hang among them (the woods) and then descend on the village and lowlands again.” Also, during the l8th century, the Manor House was reduced in size and made into a farmhouse, presumably after the last resident Lords of the Manor, the Weldons, left in 1731.

Life in l8th century Swanscombe can be gauged by events such as the suicide of, John Kivell of Northfleet. Kivell hanged himself in Swanscombe Woods and was buried “in ye highway leading to Northfleet” on 21 October 1703. In 1721 a parcel of land in the High Street at Greenhithe, was given by Lady Swan for the benefit of the poor. As mentioned, a workhouse also existed from the 1760s.

A glimpse of pre-industrial Swanscombe can be gained through its folklore. Three stories of old Swanscombe are:

� The Virgin’s Garlands

� Clapper Napper�s Hole

� The Anchor from Heaven.

In the nave of St Peter and St Paul’s church hung, until the mid l9th century, funeral garlands which were carried before the coffin of a virgin who was buried in the parish. The garlands were placed on the coffin during the funeral and afterwards hung on a beam in the church as trophies of the victory over lusts of the flesh and as a symbol of everlasting life.

Clapper Napper’s Hole was a denehole on the southern edge of Swanscombe Woods and was divided into several caverns below ground. Many stories grew up about the place, no doubt embroidered by the gypsies who occasionally camped there. A kidnapper and robber, the terror of the locality, was said to have lived there in medieval times. The cavern is supposed to be haunted by a gentleman who was sent below playing a musical instrument in order to show people above ground the length of a tunnel, Above ground his companions followed the music or beat until it suddenly stopped, the man was never discovered. Similarly, a fortune-teller once inhabited the pit and told a youth, after reading his palm, that he would be a murderer. The youth, rather than face this awful prospect drowned himself and is supposed to haunt the cave. Legends concerning the pit being used by ancient Britons also abounded – the romance of the stories, coupled with the beauty of the surrounding landscape, made Clapper Napper’s hole a popular visiting place.

Finally, the hinges on the north door of St Peter and St Paul’s church are supposed to have been made from an anchor, which appeared one day descending from the clouds. A man, dressed in sailors clothes, then lowered himself down the chain, in order to free the anchor which was stuck behind a tombstone. The locals grappled this unfortunate man, who drowned even though on dry land while he was being held down. The chain from the clouds, was cut by the vessel, out of sight in the sky, and the locals used the anchor to make the church door hinges. The Blue Anchor public house opposite the church may be a reference to this curious tale.

An account, in the Gentleman’s Magazine of May 1803, tells of St Peter and St Paul’s church before the Victorian restoration. The structure consisted of a square tower of flints and an octagonal spire. This spire was struck by lightning on Whitsun Tuesday evening in 1802. The lightning passed down the spire into the church, damaging the monument of Dame Elinor Weldon and filling the church with a stench of sulphur but not damaging the church further. The nave of the church had a flat lead roof but the chancel had a pitched roof with tiles. There was also an old clock in the east wall of the tower. Inside, the west end had an oak gallery dated 1771.

Swanscombe was a picturesque place on the eve of industrialisation. Sparvel-Bayly, writing c1870, described it before the cement factory: “The woods on the heavy uplands, the long leafy lanes, the picturesque cottages and plenty homes of squires and yeomen … Swanscombe was once a charming village on the steep banks of the Kentish shore of Father Thames.“

On the eve of the industrial era, Swanscombe’s population was 908 (in 1821), which had risen from 763 in 1801. It steadily increased after James Frost founded his cement factory, on a site on the edge of the marshes adjoining Galley Hill, in 1825. People from the neighbouring parishes and towns and even outside areas came to Swanscombe for employment. In 1833 Frost sold his interest in the cement works to the firm of Messrs Francis, White and Francis before the whole business was taken over by John Bazley White and Sons. White’s produced “Portland Cement” -a superior product to Frost’s “British Cement”. The cement works had a tremendous effect on the parish and as the works grew in size, capacity and efficiency, so its all-pervading influence on Swanscombe developed. To begin with the factory was small and the chalk and clay pits associated with it were similarly small. After the 1840s the Galley Hill area, which was closest to the works, began to develop with housing and Bazley White founded the Galley Hill Elementary School in 1858. The northern part of the High Street developed during the 1850s, the public house called “The Alma” refers to the Battle of the Alma during the Crimean War of 1853 – 1856. It was also during these early years that Bazley White had his concrete house built at the entrance to the cement works. The house was one of the very first to be largely constructed of concrete and it resembled a Jacobean/Gothic mixture in its architecture, complete with concrete cavalier statues, gables and oriel windows. It became the offices of Swanscombe Urban District Council 1926 – 1964, and was demolished later in the 1960s.

By 1868 Swanscombe was still a predominantly rural community with many acres under hops and several oast houses in the Swanscombe Street and Milton Street areas. However, Swanscombe Manor, which consisted of most of the land south of Swanscombe Street including the woods, with much land to the east and north of the villages, was sold for �40,000 to Thomas Bevan, one of the cement magnates. This sale signalled the future of much of the arable and woodlands, which would, over the next century, be largely excavated for chalk and clay, thus surrounding Swanscombe with the huge chalk pits that exist today. An example is Baker’s Hole to the east of Stanhope Road, which increased from a small chalk pit in 1873 to the giant valley, which existed by 1960.

The increasing industrialisation of the village, coupled with the pollution and unsightly appearance of the pits and factories infuriated some of Swanscombe’s older families who, under the leadership of S C Umbreville of Ingress Abbey, attempted to have the cement works closed by court action. This effort signalled the last struggle of old Swanscombe against the new industrial creation. The pro-cement lobby was well organised under the Rector of Swanscombe, the Reverend T H Candy, and consisted of a huge march and rally, which met at the Rectory Meadow in Swanscombe. The procession consisted of some 5,000 people from Stone, Greenhithe and Northfleet in addition to Swanscombe. The marchers were cement employees fearing for their jobs with banners and loaves of bread on sticks symbolising their daily bread provided by employment. Shopkeepers, shipping personnel and others joined in led by brass bands. This monster rally on 24 August 1874 eventually persuaded Mr Umbreville and his allies to drop their case.

Contemporary with the cement factory struggle was the chronic state of St Peter and St Paul’s church, which had received little restoration since the 18th century. The Reverend Thomas Candy, rector 1868-1888, undertook to raise money for the restoration on a subscription basis and the repairs were to cost in excess of �3,000. Candy’s own efforts raised only �200 but Sir Erasmus Wilson (1809 1884), the eminent skin specialist and the man who brought Cleopatra’s Needle to London, stepped in with an offer of �2,000. Wilson’s father, also a medical doctor, lived in Dartford and Greenhithe and Sir Erasmus himself had been taught by the Rector of Swanscombe, Reverend Renouard, while living at Greenhithe and attending St Peter and St Paul’s church. Sir Erasmus’s generous gift went to restoring the tower and nave and resulted in further donations including one from White’s cement works. A new north porch, was paid for, by the Erasmus Wilson Lodge of Freemasons from Greenhithe. The restored church was officially re-opened on 31 October 1874. The restoration included a new oak roof, new pews replacing the l7th century boxpews and the retiling of the floor. The clock also disappeared at this time.

Swanscombe itself was rapidly developing. As early as 1853 a meeting was held under the chairmanship of James Harmer, to discuss gas street lighting for Swanscombe and Greenhithe in view of development. In the 1860s further development occurred, many houses in the High Street are dated 1866 while those in The Grove date from the 1870s. As the population increased so existing streets became urbanised and completely new ones were built. The population in 1821 (before the arrival of cement) was 908, by 1851 this had risen to 1,763 and to 6,577 in 1891. The extra people needed housing, education, and services such as gas, sewerage, and later, electricity. In addition, the associated religious and cultural life, which grew with the influx of people, transformed the old rural village into a small town as much as the physical development. Between 1870 and 1898 on the land opposite the church and north of Swanscombe Street, there rapidly sprang up:

� Hope Road � Harmer Road

� Albert Road � Herbert Road

� Castle Road � Castle Street

� Eglington Road � Sun Road

Older roads, such as Church Road, were soon filled with these new terraced workers’ cottages. Swanscombe Street was losing much of its rural appearance by 1897, while Milton Street and Milton Road were likewise being covered with terraced houses. Milton Road’s dated houses are Emily Cottages (1877) and succeeding rows of housing illustrate how this road developed:

� Kirteen Terrace (1881) � Victoria Terrace (1882)

� Myrtle Villas (1889) � Eagle Villas (1902)

� Claridge Villas (1903) and

� Several others preceding World War One.

Swanscombe’s schools grew rapidly with the growth of population. The original national school was founded in 1844 at Howe Hill in Stone before being sold c1871 and rebuilt as the Greenhithe National School in 1873. Galley Hill School was built in 1858 and originally held a mechanics’ institute, this establishment being supported by the White’s Cement Factory whose employment was drawing many workers into the Galley Hill area. During the 1860s and early 1870s Mr Umbreville of Ingress Abbey rented to the village a large house opposite Swanscombe Street in Stanhope Road for use as a school. A school was associated with the Congregational church, which used to stand in Milton Road.

Swanscombe received its own purpose-built school in 1878 with the opening of Manor Road. The development of the village during the 1880s and 1890s between Church Road and Stanhope Road, plus further developments along Swanscombe Street and Milton Road produced more pupils and as a result an infants’ school was opened at Harmer Road in 1893.

Swanscombe’s cultural and political character was changing with the growth of working class housing and this period of the late l9th century resulted in the last of old rural Swanscombe being replaced by much of what we see today.

In 1847 the Swanscombe Literary Institute, was founded by White’s Cement Factory. This society, in 1887, had 87 members and met in the Reading Room of All Saints Church, Galley Hill. Private education was offered in addition to the schools mentioned, an example was the Kirton Private School run by Mr and Mrs Helliott. Swanscombe and Greenhithe Cricket Club was founded in 1880 and Swanscombe United Football Club and other soccer teams began in this period. The Swanscombe Liberal and Radical Association were also active and held a supper in honour of Gladstone’s birthday in 1887. In 1894, when Swanscombe Parish Council was created as part of local government reform, 15 councillors were elected out of 32 candidates and the Labour and Progressive Party “were early astir at Swanscombe” on that occasion.

In religious matters, the late l9th century was a golden age for Swanscombe with Anglicans, nonconformists and Catholics all represented in various churches and chapels. The mother church of St Peter and St Paul had been joined in 1856 by St Mary’s Greenhithe and in 1881 by All Saints church at Galley Hill. All Saints was largely paid for by White’s Cement Factory and was “the outcome of the desire of the proprietors of the Portland Cement Factory of Messrs J B White and Sons to promote the spiritual welfare of those dependent on the industry for their livelihood“. The present All Saints church was designed by Norman Shaw and dates from 1895, the old building becoming a church hall. Other religious institutions included:

� A Salvation Army barracks in Stanhope Road;

� A Primitive Methodist chapel in Milton Street (1888);

� An independent dissenting chapel at Swanscombe Cross (1851);

� A Congregational church, which existed in Milton Road from at least 1840 until demolished later in the l9th century.

A Strict Baptist meeting room was opened in Milton Road in 1901, but moribund by 1932; there was also a Wesleyan Chapel in Church Road.

The cement industry, which began Swanscombe’s industrialisation, was now well established, with excellent communications via road, rail and river. Cement was now established in Greenhithe, Stone and Northfleet. The opening of Tilbury Docks in 1886 and the development of paper and engineering industries in Gravesend, Northfleet and Dartford added employment. In Swanscombe itself, the other major employers were, the New Northfleet Paper Mill, built between 1883 and 1886 for Carl Ekman, a Swedish chemist, and the Britannia Cement Works, which was just inside the Swanscombe boundary with Northfleet. These major employers were soon followed by all the grocers, hairdressers, coal dealers, builders, bakers, doctors and teachers needed by the new workforce. Meanwhile, traditional farming and the newer market gardening were still significant sections of Swanscombe’s economy during the late l9th and early 20th centuries. In 1887, the Northfleet and Swanscombe Brickfields Company, which had helped to build many of Swanscombe’s new houses, closed down. Finally, Moore’s Mineral Water Factory in Milton Road was founded in 1879, giving local people work and supplying many local shops in the area with drinks until it was closed in 1968.

It was during the 1890s that Marie Stopes (1880-1958), the pioneer in family planning, lived at Swanscombe as a child with her parents and family. Marie’s father, Henry Stopes, had a great interest in prehistoric archaeology and he rented the Mansion House in Swanscombe Street. The Stopes lived in this Elizabethan mansion with its numerous panelled rooms and high-walled garden from 1894 until 1899. Marie’s childhood collecting archaeological specimens and various plants from Swanscombe Woods gave her a lifelong interest in botany.

Swanscombe’s increasing population necessitated a new cemetery, which was opened in 1885 as a burial ground, at a cost of 493. In 1895 and 1896 a scandal broke out concerning the Clerk of the Burial Ground, a solicitor from Dartford. The solicitor was accused by the Rector of Swanscombe and a member of the parish council of making numerous errors in the burial records and even getting the various plots muddled in his ledgers. The story was published in “The Star” newspaper and showed that the solicitor had too many similar jobs and was overworked by his numerous contracts. Swanscombe decided to take over the cemetery’s administration and later built a mortuary chapel in 1905. In 1902 Henry Stopes died and was buried in the cemetery.

On the evening of 14 August 1902, during a terrific thunderstorm, St Peter and St Paul’s church was struck by lightning, which caused a fire in the tower and the nave. The fire brigades of Swanscombe and Northfleet were quickly on the scene but the low water pressure hampered their efforts. The damage was considerable, the bells melted in the heat and the tower and nave were largely gutted. Falling timbers destroyed the ancient chalk font and the rood screen, but amazingly, nearly all the other treasures were saved. In September 1902 the church’s restoration was begun with the same architect who had restored it in 1873, Mr J Bignall. The new restoration cost �4,000 and was completed by June 1903. A new peal of eight bells was dedicated in March 1904.

Transport facilities to growing Swanscombe improved on 22 September 1902, when the newly constructed electric tramway, from Denton through Gravesend and Northfleet reached the parish. The trams ran along the London Road with stops at the George and Dragon on Galley Hill and Craylands Lane, where the trams turned around and returned eastwards. The tram conductors shouted “Holy City” when stopping at Swanscombe. This curious name was linked to the fact that Swanscombe was surrounded by pits or holes and “Holy” was really “Holey”. The terminus at Craylands Lane (Swanscombe Cross) was only 1� miles from that of Dartford’s trams at Horns Cross. The South Eastern and Chatham Railway stopped any attempt at linking the two tram systems, as this would have rivalled their monopoly. In order to placate local opinion, the Railway Company opened a railway halt at Craylands Lane in 1908. The halt’s position was on the edge of Swanscombe and not well used until moved to its present position in 1930.

In Swanscombe itself the Parish Council was agreeing to have the main roads tar-paved in 1908 and the same year saw the fire station in Church Road opened. The room above the fire station was used by the council for its meetings after it was built on in 1922

The growth of Swanscombe’s population was matched by problems of housing, sewerage, water supply and other services. As part of the self-help spirit, Swanscombe founded a Land Club. By 1911 the Land Club obtained allotments for rent from the parish council and then re-rented them to members. Animals were also kept, especially pigs and the Land Club also pushed for more housing to be built for workers. At the turn of the century Swanscombe was a curious mixture of an urban and industrialised village growing into a small town, but still surrounded by much countryside and with many of its rural buildings still intact. The fruit orchards gave rise to a jam factory near the Manor House, with many meadows and small streams running alongside roads. Some of the roads being built from the 1860s onwards were on the site of old footpaths, e.g. Sun Road, Church Road, Gunn Road and Park Road. Hard times brought unemployment and soup kitchens with much neighbourly co-operation. Good times included:

� Sunday treats � football

� Walks � picnics and elections.

It was during the pre-First World War period that Phyllis Bottome lived with her father, the Reverend William McDonald Bottome, vicar of All Saints, Galley Hill, 1900-1913. Phyllis is remembered as a novelist, essayist and biographer; her works include The Mortal Storm (1937), Life Line (1946) and Under the Skin (1950).

The Swanscombe branch of the Borough of Gravesend Co-operative Society was opened in the High Street in 1913.

The cement industry reorganised in 1900 when the independent companies combined to form the Associated Portland Cement Manufacturers Ltd (APCM). Frederick Anthony White, head of Swanscombe Cement Works, became the first chairman of the APCM and Swanscombe’s factory underwent considerable improvement with the installation of 16 rotary kilns of 80 feet in length and six feet five inches in width. Despite serious flooding of the works in 1904 when the Thames burst its banks, Swanscombe’s cement industry was rapidly eating up the supplies of clay brought in from the Medway and consequently began to dig for clay at Swanscombe Woods in 1909.

The outbreak of World War 1 saw much volunteering for the services resulting in a serious shortage of labour. Women were employed in the cement and paper factories while, after normal shifts finished, men and women would continue to work making extra munitions in temporary workshops. Ingress Abbey was used as a hospital for the wounded while part of Knockhall Lodge became a convalescent home. Food was grown on football pitches, and at the end of four years of slaughter, Swanscombe had lost some 106 men.

The 1920s brought much unemployment and there was a slump in the cement industry. Modernisation of the cement works was undertaken in order to decrease production costs. The new method of removing topsoil over chalk was by water jets washing soil into neighbouring pits. The population continued to grow from 7,693 in 1911 to 8,494 in 1921. In 1922 a sewerage scheme commenced which was completed in 1926. Many houses still had cesspools and water contamination was a real problem. In 1923 the Electric Cinema was opened, later renamed the Jubilee. It was demolished and replaced by the Wardona in 1939. The old Watling Street on Swanscombe’s southern boundary was opened as a new bypass in 1924, which relieved both the unemployed who built it and the traffic along the lower road.

Swanscombe, despite its continual development, was still a parish council within the Dartford Rural District. Swanscombe’s housing needs, as well as sewerage and electricity supplies, were concerns that many on the parish council felt that they could better organise themselves. Swanscombe, as the parish with the largest population and the best rateable value with its industry, resented having to “take its turn” in rural district policies and having to help pay for council services in neighbouring parishes. Consequently Swanscombe applied to become a separate local authority and this was achieved in 1926, when the Swanscombe Urban District Council was founded. This council, which consisted of 18 councillors and three wards, ran the town’s affairs for the next 48 years.

SWANSCOMBE URBAN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1926 – 1974

Now that Swanscombe had urban powers and was a separate local authority, the town could fulfil the wishes it had long cherished. In 1926 the sewage works on the marshes and a sewerage scheme for the main urban area were completed. Despite this, many houses still had cesspools, which had to be pumped out by lorries or carts and on such occasions children were kept indoors for fear of disease. Almost immediately on becoming an urban district Northfleet asked Swanscombe to amalgamate with them in order to become a larger local authority offering more services to their inhabitants. Swanscombe politely turned the offer down but various schemes for union with Northfleet were suggested throughout the 1926 – 1974 period.

In 1928 Swanscombe’s cultural life was improved by the construction of a parish room at All Saints church Galley Hill, the founding of a fund to buy instruments for the Swanscombe and Greenhithe Village Band and the opening of Swanscombe Library. Swanscombe’s library, the only one of the three 1928 schemes mentioned to be still functioning, was opened in a room above the fire station in Church Road in November. The branch was open twice a week for two hours in the evening and had 1,660 books, which were changed three times a year. The library later moved downstairs to occupy its present position during 1968. A major Kent County Council project for Swanscombe, was the building and official opening in April 1928 of the Swanscombe Central School in Eynsford Road. The school was built to help house the ever-growing population of pupils and to provide a higher standard of education than that provided by the elementary schools already operating. Perhaps the greatest project for Swanscombe at this time was the Urban District Council’s housing scheme, which was to increase the population and to be an example of municipal housing to other authorities. The land was purchased mainly from APCM to the south of Milton Road, west of Church Road and north of Gunn Road. By 1929, Ames, Gasson, Stanley, Sweyne and Vernon Roads had been partially or wholly constructed.

By 1930 electricity was decided upon as a means of street lighting and further extensions to the council’s housing undertaken. As more land was acquired for housing so the council decided to create an open space in the shape of Swanscombe Recreation Ground. The “movement for a better and brighter Swanscombe”, which was the council’s theme during the 1920s and 1930s, was greatly enhanced by the official opening of the Recreation Ground on 30 April 1932.

The complex included:

� A formal park � bandstand

� Football ground � bowling green

� Tennis courts � boating pond

� Public lavatories.

In addition, a drinking fountain was unveiled in memory of Councillor E Moore by his widow.

In November 1932 a second library was opened in Greenhithe High Street. During the early 1930s there were various proposals for local government boundary changes and Swanscombe ever watchful of Gravesend’s and Dartford’s hopes to expand into neighbouring parishes, proposed to annex parts of Stone, but the boundaries remained intact and no gains or losses were realised. It was during the late 1930s that Galley Hill School was finally closed.

Another great leisure event was on 8 August 1936, when the swimming pool was opened in London Road. By 1939, Swanscombe Urban District Council could look back over a period of great advances in most areas of housing, health and services. The housing scheme had been extended during the 1930s so that Broad, Gunn, Lewis, Moore, Park and Trebble Roads had all been built. In 1938 a temporary building, which later became Swanscombe Secondary School, was constructed in Southfleet Road. In 1939 the Wardona Cinema was reconstructed, the previous building was known locally as the “Bug Hutch” because of its dilapidated condition.

At the outbreak of World War Two in 1939, Swanscombe’s population was some 8,600. The major employers within the urban district were the cement factory and paper industries, as well as smaller engineering works, farming and smaller concerns such as Moore’s Mineral Water Factory and the small jam factory near Manor Farm. The cement factory, which had been updated during the 1930s, escaped serious damage during the war, but Swanscombe as a whole was hit many times because of its position in the Kentish industrial corridor to London. The first bomb to hit Swanscombe was on 27 August 1940, when a high explosive device fell in Knockhall Chase pit.

Some of the more spectacular bomb strikes included:

� Damage to All Saints church on 18 September 1940;

� A direct hit on the Dutch tanker “S S Larenarecht” on 22 September 1940;

� Damage to the control telephone and headquarters of Knockhall Lodge on 17 January 1943

� A direct hit on an Anderson shelter on 18 January 1943.

Serious loss of domestic property occurred at:

� Knockhall Chase on 8 October 1940;

� Galley Hill Road on 30 October 1940;

� Trebble Road and Milton Street on 5 November 1940.

On 10 November 1940, a direct hit on the Morning Star public house in Church Road caused the death of 27 people. The same raid damaged houses in Sun Road, Vernon Road and Castle Street. The first V1 flying bomb to hit the British Isles fell near Watling Street in Swanscombe on 13 June 1944; other flying bomb attacks included damage to Alkerden Farm on 25 July 1944, and a major hit on Taunton Road on 30 July 1944, when 61 families were made homeless. Finally, on 16 August 1944, farm buildings at Western Cross were damaged by a flying bomb. World War Two ended with Swanscombe having lost 63 civilian casualties, compared with Gravesend and Northfleet’s 36 and 40 respectively. Swanscombe had 93 properties destroyed compared with 45 in Gravesend and 35 in Northfleet. A small prisoner of war camp, which stood on a site in Swanscombe Street, housed German prisoners, who helped pick fruit and crops and often gave fruit to the local children. Some Swanscombe girls later married former prisoners.

Swanscombe Urban District Council set about rebuilding the damaged areas and they quickly erected prefabs. During the post-war years the council continued with their building projects: by 1949 Alamein Road, Bodle Avenue and Leonard Avenue had been built. The council itself had become more professional, especially with the appointment, in 1942, of the first full time clerk, after the previous deputy clerk had been sent to prison for two cases of fraud. Efforts to improve further the town’s housing and recreation facilities shaped policies pursued throughout the 1950s and beyond. In 1950 the council obtained Bushfield, an area south of Gunn Road, as an extra recreation facility. During the ‘Festival of Britain’ week in September 1951, several activities were carried out on these fields where fairs once stopped. Bushfield was later developed. As facilities improved and housing expanded, so even more of rural Swanscombe disappeared and farms were being sold for development or else being destroyed by chalk quarrying. The cement factory underwent further modernisation and even the serious flooding of 1953 did little to disrupt production. In 1958 the Wardona Cinema in Ames Road closed and was later demolished. By 1959 Childs Crescent, Wallace Gardens and Wright Close had been built.

The 1960s heralded a great period of expansion and redevelopment in Swanscombe’s housing. The council purchased Manor House Farm and surrounding grounds. Disgracefully, with features dating the farmhouse from several periods, it was demolished; the village pond was filled in and the farm’s grounds landscaped into Manor Park. The manor house was replaced by hideously ugly council offices in 1964 and these, after only 25 years, have been demolished. On 2nd October 1965, Manor Park was officially opened and also, in the same ceremony, the “Invicta” monument, commemorating the meeting of William 1 with the Kentish army, was relocated next to the new council offices from its original site along the A2. The new and present fire station was opened in 1966 on a site in The Grove. Swanscombe Urban District Council’s first development built with central heating was opened at Ingress Gardens in 1967. Also in 1967 the twinning of Swanscombe and Viby in Denmark was mooted, but this was never carried out. The same year saw the closing of Harmer Road School. Throughout the 1960s there were various murmurs of local government reorganisation and amalgamations, all of which Swanscombe Urban District Council opposed. In June 1968, Moore Brothers’ Soft Drinks Factory closed down. By 1969 further housing development had taken place:

� Bushfield Walk � Butcher Walk

� Gilbert Close � Keary Road

� Madden Close � Mitchell Walk

� Munford Drive � Rectory Road.

Craylands Square was to be redeveloped from 1969, replacing the Victorian and early 20th century housing in that area. One of the many casualties of the obsession with redevelopment at this time was the old Blue Anchor public house, which was demolished and rebuilt in 1965. In 1970 the new cement factory at Northfleet was opened and, as a result, Blue Circle closed all their other factories in North West Kent, except Swanscombe which made special cements. The craze for demolition begun in the 1960s destroyed almost every old building in Swanscombe – the last remaining weatherboard cottages, in Milton Road, were demolished in November 1971. Sweyne Primary School opened in February 1971, after further internal reorganisation at Swanscombe School in Southfleet Road. The old Harmer Road School was turned into a Youth Centre and a new sports pavilion opened in October 1970. By 1974 Swanscombe Urban District Council, having continued to build on its existing estates had added Durrant Walk (1970) and Irving Walk (1971) to the housing stock. On 1 April 1974, local government reorganisation came into force; Swanscombe Urban District Council was abolished to become a parish council under Dartford District, just as it had been before 1926.

RECENT SWANSCOMBE 1974-1996

The new Swanscombe Parish Council, being the largest within Dartford District, pushed for facilities planned by the old Urban District Council. In 1975 squash courts were opened in The Grove and the Swanscombe Church Centre was opened by Lord Astor of Hever and blessed by the Bishop of Rochester on 26 April that year. Redevelopment of part of Swanscombe High Street and London Road in 1976 created a light industrial estate. In 1977 Gravesend Church Housing Association opened a �270,000 development next to All Saints church, Galley Hill, which had itself been made redundant by this time, having been first closed by the Church of England and later by the Roman Catholic Church. The 1970s saw various developments and building projects, which improved facilities for many sections of the population, such as pensioners and youth. In 1981 Swanscombe Parish Council was upgraded to Swanscombe and Greenhithe Town Council and thus elected its own mayor for the first time. The population in 1981 was 8,876, which was a decline from the 9,174 of 1971 due, in part, to redevelopment of housing and some loss of population to neighbouring areas. 1985 saw the Jubilee Celebrations in Barnfield Pit, of the discovery of the first fragment of the famous Swanscombe skull. A special plinth, unveiled by television personality Magnus Magnusson, provided a lasting memorial.

Swanscombe Urban District Council’s ugly offices were demolished and the park surrounding the site redeveloped in 1989 – 1990. The new Swanscombe Centre was opened in Craylands Lane on 22 September 1989 and this includes council offices with sports facilities. In November 1990 Blue Circle closed Swanscombe Cement Works after 165 years, killing off the creation that caused Swanscombe’s industrial growth. The early 1990s also saw the conversion of the empty All Saints Church at Galley Hill into flats. Redevelopment caused a large influx of private housing while politics led to the closure of Swanscombe Secondary School in July 1992 leaving the townsfolk bemused and angry. In 1998 a new secondary school, known as Swan Valley was built on the site of its predecessor in response to recent development and the likely impact of future proposals for the area. Manor Road Primary School left its Victorian buildings for a newer home in 1993. Government policy of allowing massive development in the area means that Swanscombe Marshes and the area bordering Northfleet in the Ebbsfleet valley are earmarked for huge building projects including an international rail terminal. Swanscombe is changing and the future heralds overwhelming differences changing the pervading industrial culture of the town.

It is hoped that this short account of Swanscombe’s fascinating history will illustrate to natives and visitors alike, the wonderful slice of Kentish heritage that is Swanscombe’s past.

A fabulous Samhain weekend is over and the Celtic new year begins. The year of 2016 marks twenty years since I began a personal spiritual journey in complete contrast to the religion I was raised within. The excitement of my first awakening will remain a prominent memory as I put aside past indoctrination and summoned the courage to explore an alternative path.

I once received a warning from a renowned Pagan Priest who used to reside in London to beware of “space cadets” and take time to find the right path. As it was an exciting time, I was eager to acquire as much knowledge as possible and experience everything! (Since writing this, he has sadly passed away, I am so grateful for his advice).

During the early days I worked alone and the first rituals I performed felt familiar to me. After a year of personal study and research I took the step of self initiation. This was and still is, the most important step of my development, a private dedication between no one but myself and the ‘powers that be’.

After experiencing the intense energy one person could raise within a sacred space, I contemplated working within a group. I replied to an advertisement in the Pagan Dawn magazine for new members to join an Egyptian group. It was a different way of working and the energies raised were extremely potent, resulting in some astounding experiences. I met two members in this group who became genuine and constant friends.

Whilst gaining experience in working within various groups I also taught a group of friends how to conduct their own rituals. I first met them when they attended my Reiki courses and discovered they also had an interest in magical work.

A while later, entering the Morris dancing world introduced me to Wiccan Priestesses and I worked with a Gardnarian group for a while. Their rituals were happy, joyful occasions and we met regularly at my home. I set up a larger altar for this purpose and prepared a space to accommodate five group members.

I was later initiated into an Alexandrian group that honoured Egyptian deities. The training and rituals were well structured, and it was then, I discovered that the Wiccan religion originated from the 1950s. This was rather disappointing as I desired to learn about the ancient ways rather than a modern belief system.

I eventually left the Alexandrian group and a few years later replied to an advertisement asking for members to join a “Cornish” Old Craft group. I communicated with the person who placed the advertisement, suggesting we could correspond and meet one another during the following six years before my move to Cornwall. They could then assess whether I would be the right type of member for their group.

I was in my thirteenth year of spiritual development when i moved to Cornwall in 2008. I did not join the Cornish Witchcraft group after all as the ‘powers that be’ provided the opportunity to meet Cassandra Latham in 2009. I then found the Old Craft and ancient ways I had searched for. It was easier for me to connect with the energies of land and sea in Cornwall than in the busy area of London. There are however some beautiful sites in Kent such as the Coldrum Stones that were a few miles away from my past place of residence.

Moving into a new community is not as easy as one thinks. Genuine people are few, but when you do find them, they are invaluable. Others can be rather territorial and if they choose to dislike you, nothing you do or say will change their minds. I have learnt that some think a person’s talent or capability is not important unless they associate with the right ‘clique’ or are born in the ‘right place’. This is probably why some allude to a ‘birth connection’ within Cornwall to feel more accepted. I am however proud to be a Kentish Maid and this does not detract from my connection with Cornwall.

When one is talented at their craft, they will meet some genuine like-minded and supportive people. Alternatively, talent and success can also expose jealous detractors. Their aim is to project their own negative traits onto a target or ‘scapegoat’ to make life so unpleasant that they eventually drive them away. If one finds themselves in this situation, it is vital to remember that only a person with outstanding talent and something worth coveting will be targeted.

Cornwall has a variety of people. Some are genuine good- hearted souls who want to live a peaceful life and do all they can to help others without an ulterior motive. Some create a “fairy-tale image” and place more importance on ‘glamour’ but lack any real substance or power. Some work under the guise of friendship for their own personal gain and cast others aside when they are no longer useful. Some seek fame and fortune and try to discredit others whom they consider a threat.

I now believe the ‘demonic forces’ religions speak of are actually within the personalities of some who use and abuse belief systems to feed their egos in order to gain power over others. It is sad these organizations scapegoat a spirit being rather than take responsibility for their own thoughts and actions.

However, when one focuses upon the positive aspects of life, the Cornish landscape and the ocean are wonderful. They are good for the soul and to see them daily is truly a blessing.

I am now accustomed to the seasons and energetic changes. As I walked to the village church one evening I was greeted by a beautiful crescent waxing moon and the star of Venus adjacent to it, was bright and beautiful.

Nothing tastes of the sea more than a raw oyster and fresh seaweed from the shore. To awake in the morning and see a murder of crows feeding from the field behind the cottage is wonderful and to sit on beaches and cliffs listening to the music of the sea is divine.

Here in Cornwall, the beaches, coves, woodland, stone circles, holy wells, quoits and ancient buildings are nearby. Focusing on these aspects of life reminds me of how blessed I am.

My twenty-year spiritual path led me here and I have worked extremely hard. No matter where my journey in life takes me, I have fulfilled my childhood dream of living in Cornwall and learnt some important life skills and lessons from the Old Craft that will remain with me.

October is a significant time of year as Samhain approaches and the year comes to a close.

Our seasonal pumpkins are chosen with careful contemplation. The energies of these beautiful vegetables are extremely important, therefore locally grown produce is a must.

It was a yearly tradition to purchase our pumpkins at the Harvest Home auction hosted by the local public house. In the last few years the pumpkins have been few or at times been absent from these auctions.

We now have an alternative adventure. We travel along the winding lanes deep into the valley of Lamorna where a local resident sells his pumpkins at the threshold of his home.

A wonderful part of residing in a village community is that produce of other items are displayed outside one’s home along with a jar for payment. This shows trust and faith in people’s good nature and many would not consider abusing this provision. This creates positive energies for the season.

It is now time to prepare the vegetables, dust off the seasonal decorations and gather ritual items as we await the closing of a productive year.

Cassandra and I have decided to move on from providing yearly ‘in person’ workshops as we have done them for the past nine years. Here are some memorable photographs of them….

2014

We had a fabulous time with our workshops and met some wonderful people. There were many thought provoking discussions and profound experiences.

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

2023

So many adventures in the last ten years! Thank you to all of you who attended our workshops.

It was indeed a profound experience to see the Man Engine puppet created to mark the anniversary of the Cornish Mining Heritage. This fabulous spectacle attracted an audience of 7000 providing us with a comfortable and clear view of the performance.

The chanting from the audience as the Man Engine rose was powerfully evocative and as you will see in the video below. At this event they included the names of the miners who had passed as the Man Engine came to life, a significant and emotional moment that will always be remembered.

An event at Goldsithney performing with the Golowan Band accompanied by the Raffidy Dumitz band and Tros and Trey Cornish dancers.

A wonderful informative day with Andrew Langdon studying St Buryan’s stone crosses and hearing their history.

Photos – Laetitia Latham Jones

A wheel-headed wayside cross situated on the B3315 at a junction with a minor road to St. Buryan. It was discovered in a hedge 1869 and placed in a grass triangle built specially for the purpose in the middle of the road.

Read more here: Boskenna Cross – Megalithic

Tregiffian is a type of chambered tomb known as an entrance grave. It survives largely intact, despite the levelling of part of its mound to make a road in the 1840s. Entrance graves are funerary and ritual monuments dating to the later Neolithic, early and middle Bronze Age (around 3000–1000 BC).

Of 93 recorded examples in England, 79 are on the Isles of Scilly, and the remainder are confined to the Penwith peninsula at the western tip of Cornwall. They are also found on the Channel Islands and in Brittany.

Such tombs typically comprise a roughly circular mound of heaped rubble and earth built over a rectangular chamber, which is constructed from slabs set edge to edge, or rubble walling, and roofed with further slabs.

The few entrance graves that have been systematically excavated have revealed cremated human bone and funerary urns, usually within the chambers but occasionally within the mound.

Read more here: Megalithic

The medieval wayside cross-base 125m west of Merry Maidens stone circle survives well and is a good example of a natural boulder being utilised as a wayside cross-base. It has been suggested that it originally supported the Nun Careg Cross, 180m to the north east on the southern route around the Penwith peninsula. The cross base forms an integral member of an unusually well preserved network of crosses marking routes that linked the important and broadly contemporary ecclesiastical centre at St Buryan with its parish. The routes marked by this monument are also marked at intervals by other crosses, demonstrating the major role and disposition of wayside crosses and the longevity of many routes still in use. The monument includes a medieval wayside cross-base situated on the verge at the junction of a path leading to St Buryan with a road along the southern coastal belt of Penwith. The wayside cross-base is visible as a large, rounded, rectangular block of granite. The cross base measures 0.83m north-south by 1.22m east-west and is 0.45m high. The rectangular socket in the top measures 0.36m long by 0.27m wide and is 0.16m deep.

Read more here: Historic England.

The Cornish Ancient Sites Protection Network is a charitable partnership formed to look after the ancient sites and monuments of Cornwall. We work closely with local communities and official organisations to protect and promote our ancient heritage landscape through research, education and outreach activities. CASPN representatives come from a wide range of organisations and community groups that share an interest in Cornwall’s ancient sites,

including: National Trust, Cornwall Council’s Historic Environment Service, Cornwall Archaeological Society, English Heritage, Penwith Access and Rights of Way, Madron Community Forum, Pagan Moot and Meyn Mamvro.

Read more here: Cornish Ancient Sites Protection Network

Nun Careg Cross stands beside the roadside between Lamorna and St Buryan Churchtown, one of a huge concentration of ancient crosses in this area.

Read more here: Megalithic